Your web agent extracts data successfully. Pipelines flow. Dashboards update. Everything looks operational.

Then someone notices the competitor prices don't match what's actually on the website. Or inventory counts show gaps that shouldn't exist. Or worse: a business decision gets made on data that was technically extracted but fundamentally incorrect.

When we validate millions of extractions daily at TinyFish, the hardest failures to catch aren't the ones that break your agent. They're the ones that keep it running while the data slowly becomes wrong. Extraction succeeds. The data just... drifts.

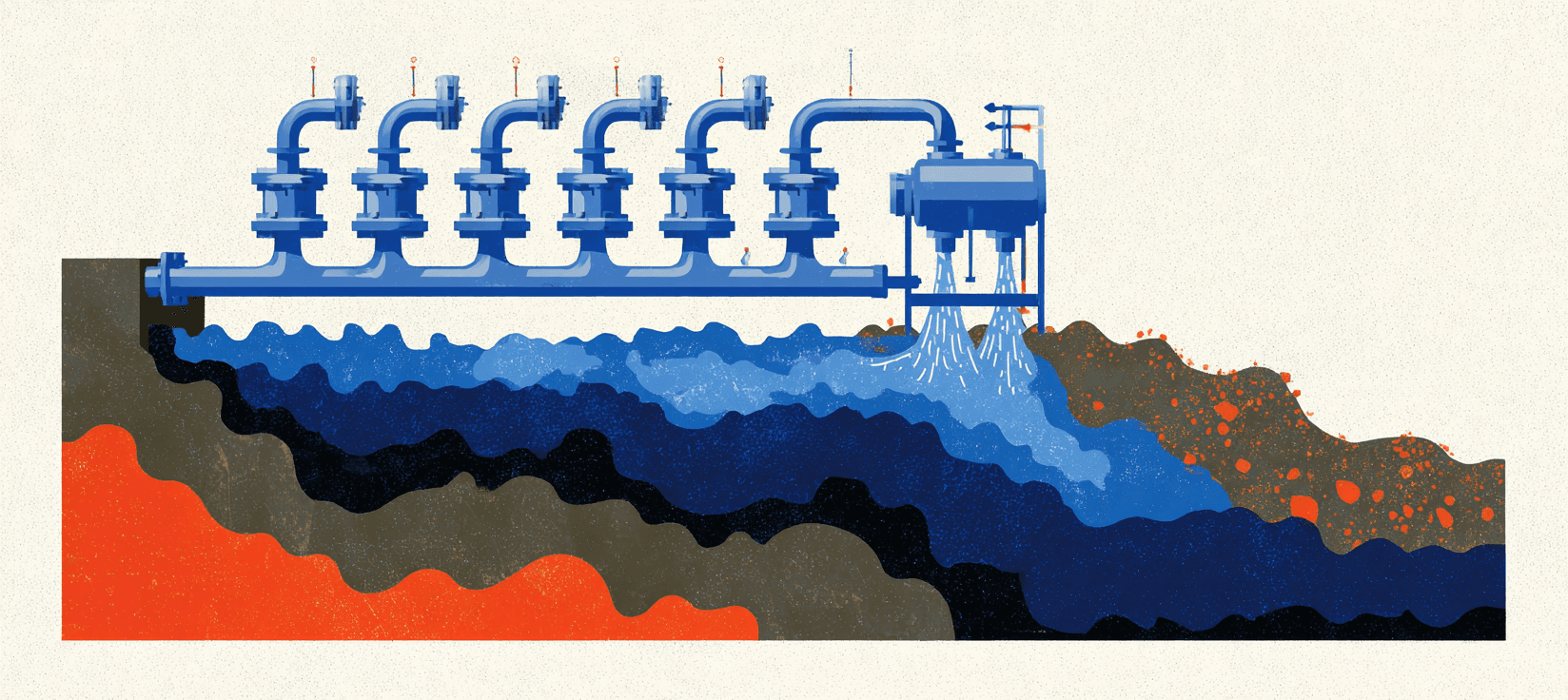

The web doesn't break cleanly. Sites A/B test their layouts, so your extraction works for 80% of users but fails for the test cohort showing different HTML structure. Authentication states change what data appears—logged-in users see member prices while your agent scrapes public rates, and you're comparing different data types without knowing it. Regional variations mean "correct" in Tokyo looks structurally wrong in London. Bot detection systems serve simplified pages to suspected scrapers, so you extract successfully but from degraded content.

Verification at scale means knowing whether extracted data actually represents what you think it does, given the web's constant shape-shifting.

Three Diagnostic Signals

Scale taught us something counterintuitive about quality problems. Early on, we focused on structural validation—did the extraction break? But most quality problems don't break extraction, they degrade it. Watching millions of extractions across thousands of sites, we learned to recognize three types of signals that announce trouble before it cascades.

Structural signals catch when HTML or DOM changes affect extraction meaning. Not the obvious breaks that throw errors—those are easy. The subtle shifts: a class name now applies to a different element type. A field moved from one parent container to another. An optional attribute became required for correct interpretation.

When you extract a price, are you still getting the same price type—regular versus promotional versus member-only—that you were getting last week? Structural monitoring answers: is the data coming from where you think it's coming from?

Statistical signals reveal when data patterns have changed in ways that suggest extraction drift. You compare new scrapes against historical baselines and watch for anomalies: a field that's suddenly null more often, a numeric range that shifted, a distribution that changed shape.

Schema validation tells you format is correct. Pattern monitoring tells you something more important: does this data look like what you've been getting? Same field, same site, but the distribution shifted—that's a signal worth investigating.

Semantic signals are the hardest because they require understanding what the data represents, not just what format it takes. A product description now includes promotional text mixed with features. A date field switched from "last updated" to "next restock." A category label means something different than it did last month.

Meaning can change while structure and statistics stay stable. Automated systems struggle here—manual review catches these shifts, but you can't review everything at scale. So you watch for the other signals and investigate when they converge.

How the Signals Work Together

A travel site redesigns their hotel listing page. Structural monitoring catches that room prices moved from a <span class="price"> to a <div class="rate">. No problem—your extraction adapts. But then statistical monitoring shows the price distribution shifted lower by 15%. And semantic review reveals those new "rates" are actually member-only prices, not the public rates you've been tracking.

Each signal alone might not trigger action. Together, they reveal your extraction is now comparing different data types—a quality problem that would corrupt competitive analysis.

This pattern holds across millions of extractions: the quality problems that matter most don't announce themselves with errors. They show up as subtle signals across multiple dimensions that, taken together, reveal correctness has drifted even though extraction still succeeds.

Building Verification That Scales

You can't manually verify every extraction when you're operating web agents at scale. But you can build systems that watch for diagnostic signals and flag problems before they cascade.

Trust your automation to extract. Verify correctness through signal monitoring. Not every field needs every signal type—that would be prohibitively expensive and mostly unnecessary.

In practice: pricing data for top competitors gets full three-signal verification because business decisions depend on it. Inventory counts across thousands of SKUs get statistical sampling—we're watching for pattern changes, not validating every number. Product descriptions get structural monitoring to catch extraction breaks, but semantic drift only gets reviewed when statistical signals suggest something changed.

What makes verification reliable at scale: catching drift early enough that you can fix extraction problems before they become decision problems. You're not aiming for perfect accuracy on every record. You're building systems that know which signals to watch and what they mean when they change.

Things to follow up on...

-

Data quality dimensions: The six primary dimensions—accuracy, completeness, consistency, validity, timeliness, and uniqueness—provide a framework for evaluating what "correct" means beyond just extraction success.

-

Website structure changes: A/B testing, seasonal promotions, and regional variations represent perhaps the biggest cause of poor data coverage or accuracy because sites constantly make small tweaks that break scrapers even when extraction appears to succeed.

-

Cost of poor quality: Organizations lose an average of $12.9 million annually to poor data quality, with 84% of CEOs concerned about the integrity of data on which they're basing decisions.

-

Validation overhead tradeoffs: Production systems balance thoroughness against operational cost through sampling validation for non-critical data and soft validation warnings instead of hard failures for non-essential fields.